If there was a contest asking which ski area best blends the best of old and new, it would be difficult to bet against Bretton Woods in northern New Hampshire. At least that’s where I’d put my money.

Sure, there are a number of worthy nominees, including New Hampshire neighbor Cranmore under the guidance of recent Hall of Fame inductee Brian McFarland and native-son president Benjamin Wilcox, or Stowe in Vermont, which now benefits from being under the Vail Resorts umbrella.

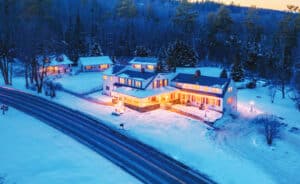

But if it were my hard-earned coin, Bretton Woods would get the nod. And here’s why. True, Bretton Woods isn’t the oldest ski area in New England, launching in 1973. And I utterly refuse to call any ski area younger than me “old.” But the area has great history, dominated by the Mount Washington Hotel, which is the flagship structure of the Omni Mount Washington Resort in the shadow of the Northeast’s tallest peak. This quintessential grand hotel dates back to 1902, built by Joseph Stickney, a New Hampshire native who made his fortune in the coal and railroad industries (the Stickney name can still be seen throughout the resort and ski area).

And that proximity, and current association with Bretton Woods, can’t be ignored. Is that cheating on my bet? Well, maybe. But when I set off from the summit of Bretton Woods on a bluebird day, taking in the wonderful views that include the grand hotel and the looming Presidential Range, I can’t help but feel that this resort offers the best of yesteryear and modern times. Clearly, I’m not the only one who has felt the same over the past 60 years.